Each Baruya belongs to one of thirteen patrilineal clans. Members of several clans live in each village, for example, eight of the clans are represented in Wiaveu: Andavakia (Gwataie's clan), Delye (Warineu's clan), Boulimambakia (Yambagwe's clan), Nunguya (Koumaineu's clan), Baruya-Kwarandai (Djirinac's clan), Yuwarumbakia, Yuwanderi, and Yuwaie. Even though precise genealogical links may have been forgotten, the members of a clan are considered to be descendants of a common ancestor. Each individual is also closely linked to his or her mother's clan. In addition, through marriage, a close relationship is established with the clan of one's spouse.

Men of the Delye and Boulimambakia clans.

Distinctions based on age grades, gender, and status cross-cut the clan divisions and provide an additional framework for the organization of society.

b. Age grade distinctions among men [Back to top]

To the outsider, the most visible distinction in Baruya society is the age grade distinction between men. As one walks through a Baruya village, one sees women, children, and mature men of all ages. The men wear a full, short sporan of reeds in front. Their backs are covered with bark cloth capes, and their chests are crossed by necklaces of dogs' teeth or orchid stem beads. A necklace crossing the chest only in one direction identifies young warriors, while necklaces crossing the chest in both directions identify married men who have fathered children. One does not see any adolescent boys. All little children are dressed like women, long reed skirts in front and a bark cloth cape behind. Among children there are no visible gender markers, and no way of knowing which is a boy and which is a girl unless one is personally acquainted with a particular child.

In the Baruya view, a boy becomes a man not merely as the result of a natural process of biological maturation, as is the case for girls, but must, rather, be created by the group. To become a man, each boy, together with his age mates, is put through a series of four elaborate initiation ceremonies. For more on male initiation.

Thus, a Baruya boy does not automatically become a man with the passage of time: it takes more than ten years of communal living with men, and four major initiation ceremonies to transform a little boy into a Baruya man. The process involves his total separation from the familiar world of family life for at least eight years.

Each initiation ceremony includes severe beating with nettle leaves. The lesson which is repeated again and again at each stage of initiation is that one must become strong, but that one's strength must always be put at the service of the group. The group identity and the knowledge which the initiates have gained of each other's strengths and weaknesses become the basis of all future action by the men. Their special relationship is henceforth marked by a taboo on speaking the name of any of one's co-initiates. This is said to be in memory of the fact that they saw each other shed tears when their noses were pierced.

A young man is educated by older men who have reached higher initiation stages than himself, and, in turn, helps to educate boys in lower initiation stages than himself. When he becomes a fully adult male, he takes part as an equal in the deliberations leading to decisions regarding activities that involve hunting, gardening, clan, village, and inter-tribal affairs.

The age grade distinctions between men are clearly indicated visually by elaborate variations in their dress. According to Baruya ideology, it is the men, rather than the women, who should dress beautifully.

c. The women's world [Back to top]

The visual distinctions made among women are much less complex than those made among men. As one walks through a Baruya village, in and among the family houses, one sees women and girls of all ages wearing long reed skirts and bark cloth capes, working alone or in groups. As one walks higher up the slope, one approaches the area of the large and beautifully constructed communal men's house. One notices that the area is devoid of women. Women are, in fact, prohibited from entering this exclusively male domain.

In Baruya mythology, it is made clear that women possess great creative power, however, unless it is directed by men, this power becomes a source of danger and disorder. This ideology is clearly expressed both spatially and behaviorally.

Moundeanga huts.

To become a Baruya woman is not as complex as becoming a Baruya man. Two major events, both biological, mark a woman's life: first menstruation and first childbirth. For more on female initiation.

The clear spatial separation of women's areas and men's areas at the edges of the village is mirrored, within the village, in each family house, which consists of one large, circular room. Only the husband has access to the back half of the room, while his wife or wives confine their activities to the front half nearest the door.

Although both men and women are involved in basic agricultural production and often work in the some space at the same time, their tasks and their tools are complementary. They plant and harvest different crops and women are not allowed to touch the axes, or the bows and arrows of the men. However, in spite of the fact that male superiority constitutes a basic strand running through Baruya ideology, women often speak up forcefully concerning the day's activities and their own affairs.

Among the Baruya, wives are not obtained in exchange for pigs or wealth, as they are among many other New Guinea peoples, but by the direct exchange of women. The Baruya consider the direct exchange of sisters to be ideal, although, if there are fewer sisters than brothers in a family, this may put brothers into direct competition with each other. Brothers, then, may split off and end up fighting each other. Brothers-in-law, on the other hand, are indebted to each other for their wives and children, and always cooperate closely with each other. When a man marries, he starts a relationship with his brother-in-law, which, for the rest of his life, will be much closer than his relationship with his brothers. It is his brother-in-law who will provide land for him to cultivate should his own clan grow so large that the pressure on its own garden land becomes too great.

Kinship is a basic, organizing factor of Baruya society: the people who have given birth to you provide you with your clan identity, and the people to whom you are related through marriage provide you with the most solid support.

People may not marry inside their own clans and, as women are exchanged between clans, their families take into consideration the necessity of maintaining as even a distribution of women among clans as possible. Marriage is frequently arranged by the parents of small children. Often close girl friends, or young men who are co-initiates, may promise that, once married, should one have a daughter and the other a son, they will give them to each other in marriage when the children grow up. From a very early age such children know they are engaged, but contact between them is limited since the boy is living in the men's world for the years preceding the marriage.

Marriage may also be arranged by prospective husbands: two young men who each have a sister agree to exchange them. This direct sister exchange is called ginamara. Of course, families do not always have an equal number of sons and daughters. If this is the case, the young man may exchange a clan sister instead of his own (such as his father's brother's daughter).

If a young man has neither sisters nor clan sisters to give in exchange for a wife, the alternative of a delayed exchange is used: he promises that when he has a grown daughter, he will give her as a bride to a member of the clan who has given him his wife. Thus, in the long run, balance can be maintained even in the face of a certain amount of demographic fluctuation.

Although it is the men, both the fathers and the prospective husbands, who overtly arrange the marriages, the women, both the mothers and the prospective brides, have a good deal to say on the matter. Mothers and daughters who are not pleased by a certain young man can put pressure on the men not to go through with their plans. A girl or boy who has not already been promised in marriage may find a partner on the basis of personal attraction.

A married couple generally lives close to the house of the husband's father, however this is not a fixed rule. Couples have a number of options, one of which is to reside near the wife's parents. When this is the case, the husband helps his wife's parents rather than his own.

As basic as the clan, age grade, and gender distinctions are, none are marked by any economic advantages or disadvantages. This lack of economic advantage is also true for the few individuals who, due to their great energy and skill, occupy positions of high social status, the most important of which are great warriors, shamans, and salt specialists.

In the years before the Australian administration brought peace to the area, great warriors were the most respected men. They were the ones who led attacks on enemy tribes and who killed enemy warriors in face to face battle. Their role of defending the tribal territory has been taken over, first, by the colonial, and, after 1975, by the national legal and police systems. Only a few of these great warriors, very old men now, are still alive.

Shamans were also responsible for the well-being of the tribe, protecting the people from illnesses which, the Baruya thought, were sent by enemy groups. Thus, both warriors and shamans protected people from enemy encroachment, the one in the physical sphere and the other at the spiritual level.

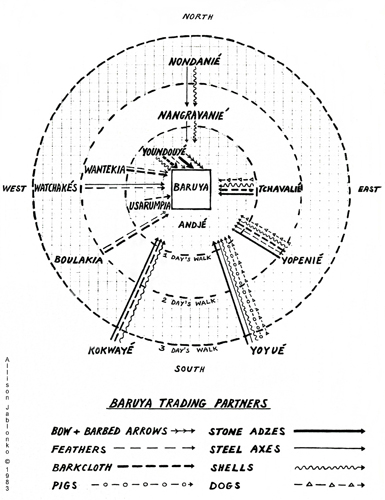

The third important status is that of salt maker. It is the salt makers who produce the salt bars which are the traditional form of currency used by the Baruya and are necessary for their economic survival. Like shamans and great warriors, the salt maker also relies upon knowledge of both the physical world and magic. This knowledge has been handed down to him from his father or uncle.

One can excel as a warrior or a shaman, one can be different from ordinary men by working as a salt maker, but there is no possibility within the Baruya system for a person to either monopolize economic goods or to command others. A great warrior who would try to wield his power over people within his own tribe, would soon be eliminated: his own tribesmen would find ways to make him fall victim to the enemy.

Older people, both men and women who have proved to be perceptive and who comment wisely in many different situations, are listened to. However, each individual must make up his or her own mind on any course of action to be taken. Projects such as forest clearing and house building require a large work force. During the many gatherings that take place during the course of Baruya daily life, there are frequent discussions and people address each other and the issues in a blunt, out-spoken fashion. Any person who wants to initiate an activity is expected to speak up forcefully and assertively. Anyone who does not do so will simply be ignored.

Baruya social structure is based upon equality among men and among clans rather than on the authority of headmen. At any point where the system could become unbalanced, such as through the possession by only one individual or group of more land or more salt fields, balance is reestablished by the sharing that is culturally prescribed among members of various clans.

a. Land ownership [Back to top]

The landscape of Wiaveu: village, gardens and forest.

Each clan territory stretches from the river banks far below the villages up to the highest ridge covered with virgin forest. This assures that members of each clan have access to all the ecological niches of the valley, from the lower, warmer, wet land, through the higher, cooler, second-growth forests, up to the highest, thick virgin forest which is carefully protected as a hunting preserve.

Though the ownership of land resides in the clan, the actual use of land is flexible. Each time new gardens are to be made, the men of each clan decide among themselves how best to apportion the land for use, often inviting people of other clans to use portions of their land. This practice allows individuals to use garden land in locations far from their clan territory and serves to even out inequities arising when the territory of a prolific clan becomes too small for the needs of its many descendants. In 1968, for example, 51% of the gardens under cultivation were being cultivated by non-owners. Most often the owners and users of a garden are connected by marriage ties. Frequently they are brothers-in-law.

b. Basic crops and econiches [Back to top]

A path by Baruya gardens.

The major staples are sweet potatoes and taro roots, which are richly augmented by green leafy vegetables, beans, and pumpkins. These crops are planted, weeded and harvested by women. Equally important to the Baruya diet is sugarcane. It is planted and harvested by men.

As with the planting and harvesting of crops, the tools which men and women can use are determined by the person's gender. Men use axes, as well as heavy wooden crowbars to split wood for fences. They also use large wooden digging sticks to take tree roots out of the ground. Women, on the other hand, use small machetes and small digging sticks for clearing, planting, weeding, and harvesting. These are made for them by a male relative: father, husband, brother or son.

Each family has several gardens at different stages of the growing cycle. Foodstuffs are harvested daily, as there is no necessity for long-term storage of foodstuffs, since sweet potatoes and taros can remain in the ground for some time after they are mature.

Gardens are generally planted on hillsides, sometimes on damp southern slopes close to the river where the ground remains cool, sometimes high on sunny slopes where the earth is drier. The Baruya consider that taro, especially, benefits from alternate planting in these different econiches.

Another econiche which the Baruya use to their advantage is the flat natural terrace system of the Wonenara Valley. Here they grow the grass necessary for their traditional salt production. This grass requires irrigation, which the Baruya have provided by digging irrigation channels from the natural springs in the area to the terraces.

Yet another econiche is provided by narrow ravines watered by steep flowing streams. In these ravines, men construct small terraces where they can grow the reeds from which are made the long, flat skirts of the women, and the short, thick sporans of the men. The men thoroughly dig the eroded soil to a depth of 15 cm. before planting, since the reeds do not need topsoil for good growth as long as they are irrigated. The flow of the water is regulated by the men who adjust and repair the irrigation channels whenever necessary. The women are in charge of the weeding, and it is they who ultimately cut the reeds and make the skirts.

c. Pig Husbandry [Back to top]

Baruya women are in charge of the only animal husbandry practiced by the Baruya — raising the semi-domesticated pigs which live in the forest areas surrounding the gardens. Since the time they are tiny piglets, these pigs are trained to come to the call of their mistress. Every evening she calls them to a fixed spot on the edge of the garden area and feeds them, chewing sweet potatoes into small pieces for the smallest piglets so they will get their share and be able to digest it easily.

As the piglets grow, they find more and more food for themselves as they roam in the second-growth forests. Eventually, grown pigs find up to 70% of their nourishment themselves. The daily feeding, however, keeps the pigs tame enough so that, when it is decided to butcher them, a man can easily get close enough to shoot them with bow and arrow.

Pork is consumed by the Baruya non-ceremonially, feasts being prepared when the people want to share "the good taste of pork" or when there are so many pigs that the women cannot manage to feed them. Piglets, like all other items, are traditionally not bought or sold among the Baruya themselves. If a family lacks piglets, friends or relatives may give them a piglet as a gift, or the husband will obtain a piglet by trade from another tribe.

3. Salt production [Back to top]

The completed salt bars have been taken out of the evaporation oven.